Have you ever thought about how Git persists our files? Although it is practically invisible, this persistence has many interesting aspects for those who like data structures.

Let’s understand how it works?

If you want to read and execute the Git commands in the post as you read, just clone the repository below in a terminal that has Git in.

git clone https://github.com/JulianoGTZ/how-git-works.git

Associative Data Structures

According to the documentation, Git is a “content-addressable filesystem”, which in practice translates into a classic associative structure of key and value.

In computer science, there are many associative structures such as associative arrays, maps, symbol tables, or dictionaries. Conceptually we are talking about an abstract data structure composed of key and value pairs, in which a given key references a value at least once.

Although mathematics is an integral part of computer science, the term association has no relation with the association property of mathematics or propositional logic.

Metaphorically it is as if Git managed to search for an element in its database similar to the way we search for the meaning of a word in a dictionary.

But what does git associate with?

Hashes, Hashes everywhere

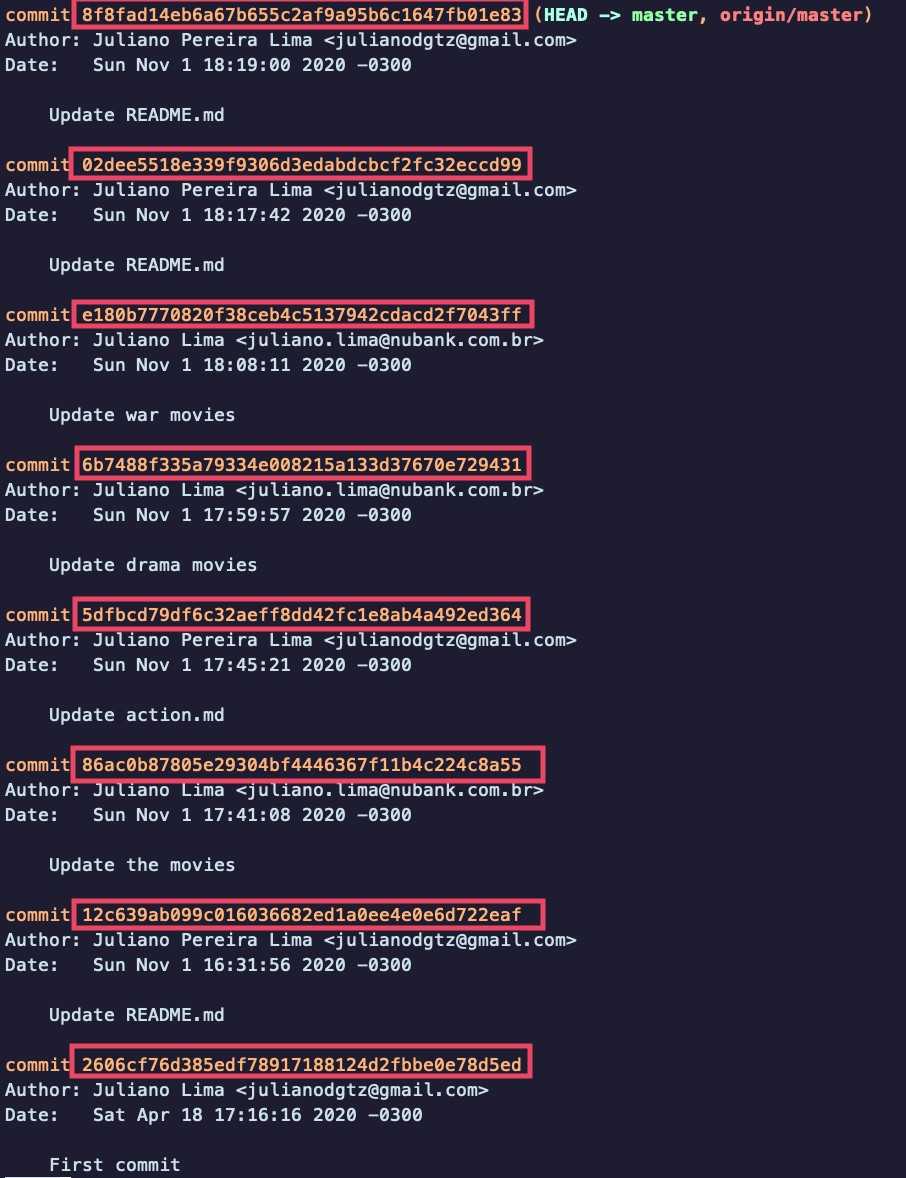

Git is guided by hashes. We can see this by running a git-log and see lots of them assigned to commits.

Conceptualizing: A hash is a fixed-length string calculated by an algorithm specialized in it (such as MD5, SHA1) where the objective is to have a single result corresponding to the input parameters (aka seed).

In the case of git, these keys can be generated from any sequence of bytes from any type of file. For each of these sequences, a key of type SHA1 is calculated.

We can play with this key generation algorithm. Just run the following command in a terminal:

$ echo "Cool article" | git hash-object --stdin

$ e41d386e3fabb637ece1e5f9a5a88b25a9515909And the result is always the same:

e41d386e3fabb637ece1e5f9a5a88b25a9515909

I had to use echo, stdin and | because we are only using the algorithm, but not operating on a sequence of bytes already known by git, as a committed file. That way we are sending a stream of bytes to git hash-object to encrypt

The result of the function is deterministic, that is, given the same input, the function always returns the same result. This is one of the mechanisms that helps to ensure that each change in your repository mapped by git is respective to what has actually been changed.

Commits

In order to talk about the next data structure we will need to understand a little more about the structure of commits:

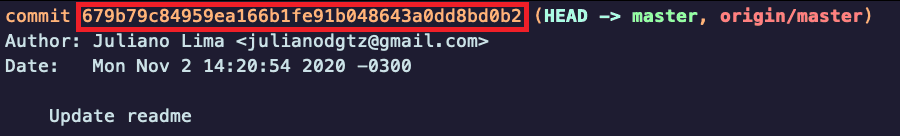

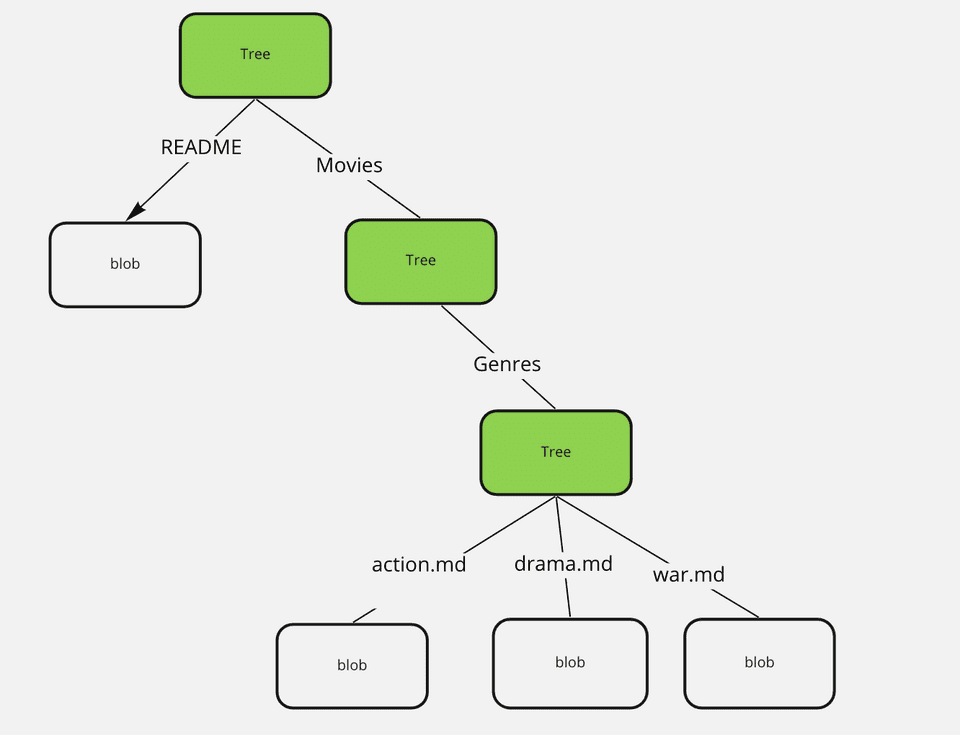

With the hash of a commit in hand, we can use a function to read its contents: the cat-file function. Just use it by passing - p (print) and the hash that we observe as parameters:

git cat-file -p 679b79c84959ea166b1fe91b048643a0dd8bd0b2

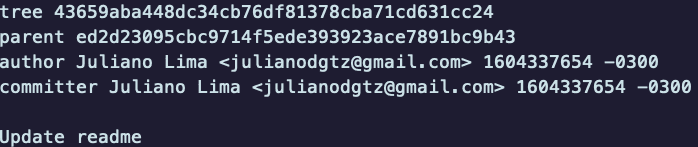

Executing the command we see the following information:

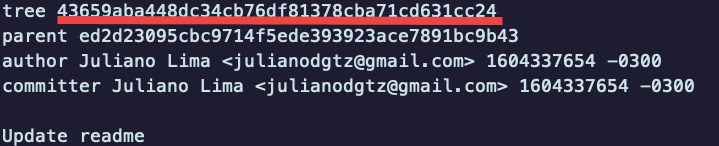

- tree: The hash corresponding to the repository’s directory and file structure (More details below)

- parent: The previous commit hash.

- author: The author of the commit (in this case, It’ me) and some timestamp information.

- commiter: The committer is the one who actually merged a specific commit. For example: if you make a pull request for a project and one of the main members merits it, you will both receive credit - you as the author and the main member as the committer. We also have timestamp information here.

- Update Readme: The commit message

We can conceptualize that the commit is a snapshot of the current configuration of all indexed files in the repository. When I say indexed it is everything that has been previously versioned or what has been versioned after the commit.

This exact picture of the repository is in the tree attribute of the commit. That’s cool but…, what is a tree?

Tree

Not far from translation, it is a reference tree. Computationally, we are talking about a data structure with different connections between nodes of information, but different from a linear structure such as an array or a list, we have depth in navigability.

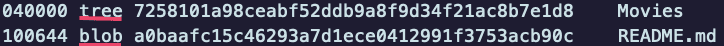

Now that we know how to see the information inside a Git hash, just run the following command:

git cat-file -p 59d80c6ce2b65acdb308058b2b0c97a4358df8f6

And we have as a result:

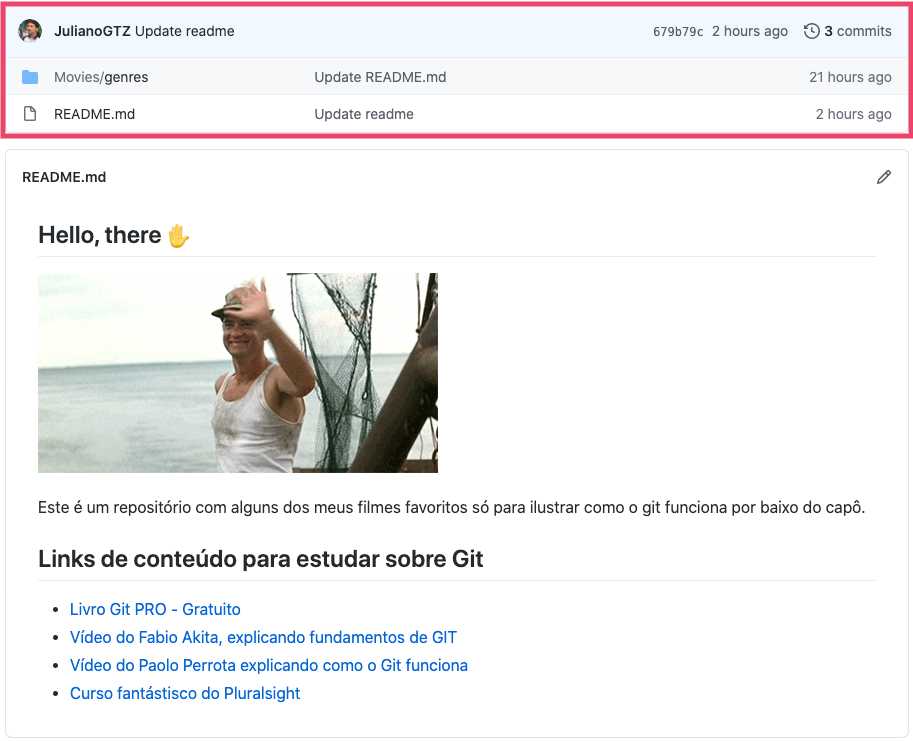

The result, although apparently not saying much, is representing exactly the structure of the repository that I am exploring as an example:

The versioning tree has two possible types of stored values:

- Blob: is any binary file in the repository. In the example above is the README.md

- Tree: A directory. In practice it is a tree that can have several subfolders and files inside.

The figure below represents exactly the folder and file structure of the repository.

We can see that the leaf node (the node at the end of the tree) will always be a Blob. In practice this means that Git does not version empty folders. A tree will only exist if there is a reference to a file inside that folder.

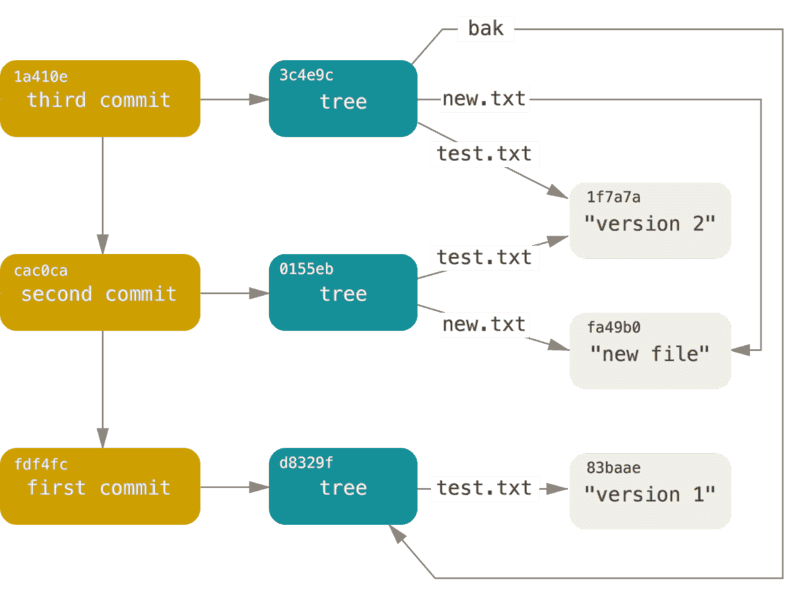

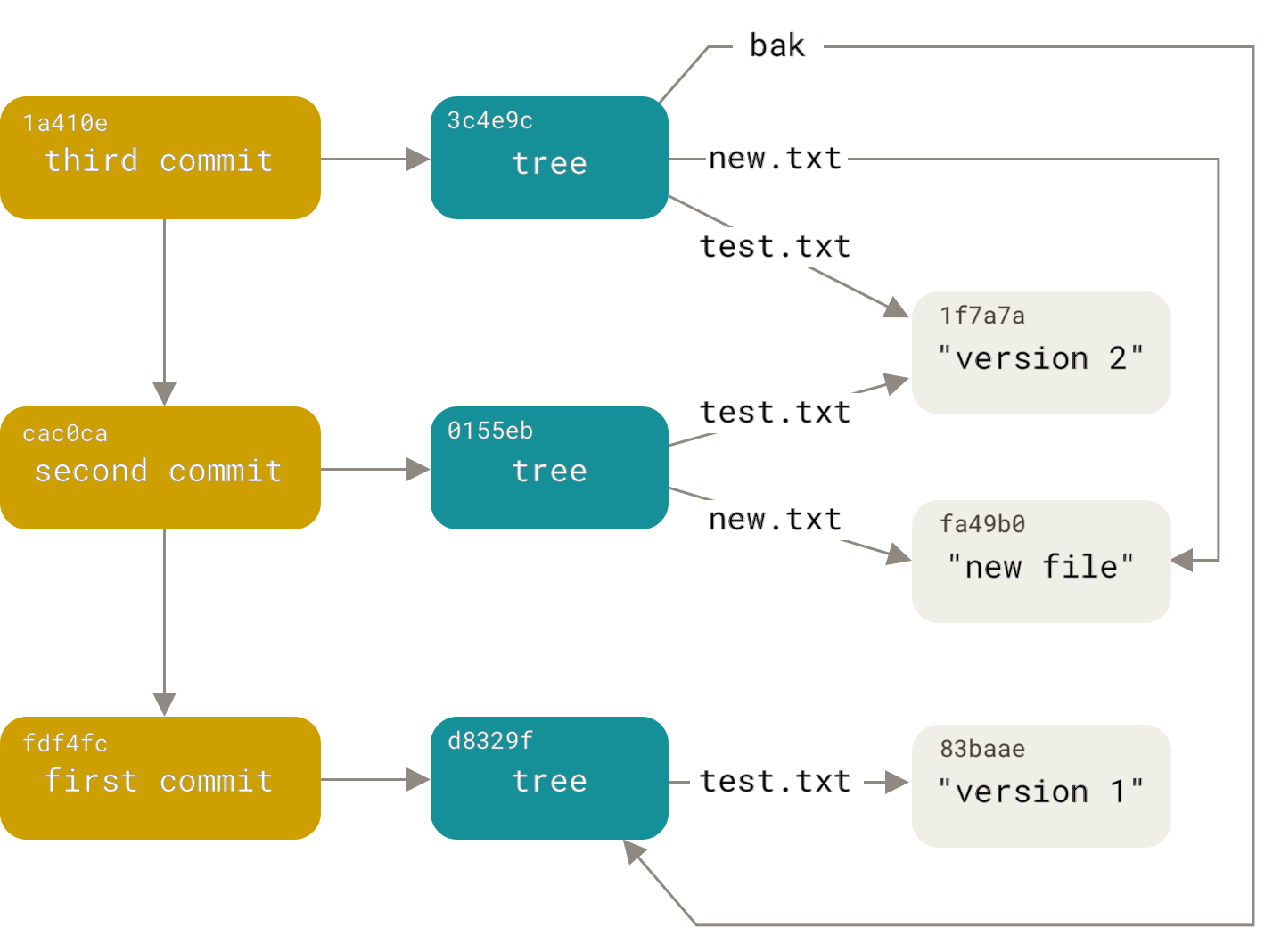

Commits are essentially references for new trees. Whenever we change a file, add a different file or rename a folder, we are also reorganizing this reference tree.

As shown in the figure presented at the beginning of the article, we are always generating new trees at each commit. As we are working on a system that uses deterministic functions which any minimal change already makes the structure different, we are always recreating new branches among the multiple possible versions of our files. The name branch makes more sense now, doesn’t it?

It is also interesting to know that git has a garbage collector system. The goal is to remove unnecessary files from old branches that no longer make sense in the repository. But how does Git evaluate this?

Given it’s a tree the git only needs to find unrelated nodes. For instance, you can use the command git gc --prune. This commands scans the versioning trees and finds branches that are no longer related to any branch of the versioning tree (Due to some merge probably)

A little bit about immutability

If you have seen any content on functional programming, you must have read the word immutability. At first, those who work with languages that don’t have native support for it may find the concept a little weird. If I’m programming abstractions like classes, interfaces, and generic functions why would it be interesting a code without variables?

Calm down, that’s not exactly what immutability is about. In fact, the concept of immutability is about making a certain value accessible even if its direct reference has changed, so the value is still accessible for computations that may need to see that value in the future.

In practice what does that mean?

The existing commands to change commits like git rebase or git change write new commits and do not change previous commits directly. When rewriting a commit we are defining new attributes such as timestamp, new author, or new changes in blobs (consequently in trees), so it’s a new commit.

We are not making a classic change in the value of a variable as in programming, but writing a new reference and preserving the old one. If this structure were not immutable each time we rebase, we would also change all references to all other branches in the repository that know those same files.

Thanks Immutability

Going Further

There are much more topics about how git works internally such as Branches, Tags, Merge vs Rebase, the three areas of Git, Fast-Forward, HEAD, and so on. I promise to write about this in future articles.

I leave some recommendations for content in case you want to understand more deeply the references of this article:

See you later o/